Agriculture Extension Education

Basic Concepts of Agriculture Extension Education

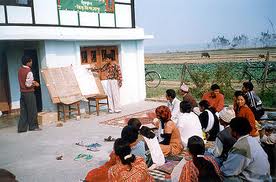

Agricultural extension was once known as the application of scientific research and new knowledge to agricultural practices through farmer education. The field of extension now encompasses a wider range of communication and learning activities organized for rural people by professionals from different disciplines, including agriculture, agricultural marketing, health, and business studies.

Extension terminology

The term extension was first used to describe adult education programmes in England in the second half of the 19th century; these programmes helped to expand – or extend – the work of universities beyond the campus and into the neighbouring community. The term was later adopted in the United States of America, while in Britain it was replaced with “advisory service” in the 20th century.

Definitions of extension

There is no widely accepted definition of agricultural extension. The ten examples given below are taken from a number of books on extension published over a period of more than 50 years:

1949: The central task of extension is to help rural families help themselves by applying science, whether physical or social, to the daily routines of farming, homemaking, and family and community living.

1965: Agricultural extension has been described as a system of out-of-school education for rural people.

1966: Extension personnel have the task of bringing scientific knowledge to farm families in the farms and homes. The object of the task is to improve the efficiency of agriculture.

1973: Extension is a service or system which assists farm people, through educational procedures, in improving farming methods and techniques, increasing production efficiency and income, bettering their levels of living and lifting social and educational standards.

1974: Extension involves the conscious use of communication of information to help people form sound opinions and make good decisions.

1982: Agricultural Extension: Assistance to farmers to help them identify and analyze their production problems and become aware of the opportunities for improvement.

1988: Extension is a professional communication intervention deployed by an institution to induce change in voluntary behaviors with a presumed public or collective utility.

1997: Extension is the organized exchange of information and the purposive transfer of skills.

1999: The essence of agricultural extension is to facilitate interplay and nurture synergies within a total information system involving agricultural research, agricultural education and a vast complex of information-providing businesses.

2004: Extension is a series of embedded communicative interventions that are meant, among others, to develop and/or induce innovations which supposedly help to resolve (usually multi-actor) problematic situations.

Origins of agricultural extension (History)

Men and women have been growing crops and raising livestock for approximately 10,000 years. Throughout this period, farmers have continually adapted their technologies, assessed the results, and shared what they have learned with other members of the community. Most of this communication has taken the form of verbal explanations and practical demonstrations, but some information took a more durable form as soon as systems of writing were developed. Details of agricultural practices have been found in records from ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia and China going back more than 3,000 years.

It is not known where or when the first extension activities took place. It is known, however, that Chinese officials were creating agricultural policies, documenting practical knowledge, and disseminating advice to farmers at least 2,000 years ago. For example, in approximately 800 BC, the minister responsible for agriculture under one of the Zhou dynasty emperors organized the teaching of crop rotation and drainage to farmers. The minister also leased equipment to farmers, built grain stores and supplied free food during times of famine.

The birth of the modern extension service has been attributed to events that took place in Ireland in the middle of the 19th century. Between 1845–51 the Irish potato crop was destroyed by fungal diseases and a severe famine occurred (see Great Irish Famine). The British Government arranged for “practical instructors” to travel to rural areas and teach small farmer how to cultivate alternative crops. This scheme attracted the attention of government officials in Germany, who organized their own system of traveling instructors. By the end of the 19th century, the idea had spread to Denmark, Netherlands, Italy, and France.

The term “university extension” was first used by the Universities of Cambridge and Oxford in 1867 to describe teaching activities that extended the work of the institution beyond the campus. Most of these early activities were not, however, related to agriculture. It was not until the beginning of the 20th century, when colleges in the United States started conducting demonstrations at agricultural shows and giving lectures to farmer’s clubs, that the term “extension service” was applied to the type of work that we now recognize by that name.

In the United States, the Hatch Act of 1887 established a system of agricultural experiment stations in conjunction with each state’s land-grant university, and the Smith-Lever Act of 1914 created a system of cooperative extension to be operated by those universities in order to inform people about current developments in agriculture, home economics, and related subjects.

Four paradigms of agricultural extension

Any particular extension system can be described both in terms of both how communication takes place and why it takes place. It is not the case that paternalistic systems are always persuasive, nor is it the case that participatory projects are necessarily educational. Instead there are four possible combinations, each of which represents a different extension paradigm, as follows:

Technology Transfer (persuasive+paternalistic). This paradigm was prevalent in colonial times, and reappeared in the 1970s and 1980s when the Training and Visit system was established across Asia. Technology transfer involves a top-down approach that delivers specific recommendations to farmers about the practices they should adopt.

Advisory work (persuasive+participatory). This paradigm can be seen today where government organizations or private consulting companies respond to farmers enquiries with technical prescriptions. It also takes the form of projects managed by donor agencies and NGOs that use participatory approaches to promote pre-determined packages of technology.

Human Resource Development (educational+paternalistic). This paradigm dominated the earliest days of extension in Europe and North America, when universities gave training to rural people who were too poor to attend full-time courses. It continues today in the outreach activities of colleges around the world. Top-down teaching methods are employed, but students are expected to make their own decisions about how to use the knowledge they acquire.

Facilitation for empowerment (educational+participatory). This paradigm involves methods such as experiential learning and farmer-to-farmer exchanges. Knowledge is gained through interactive processes and the participants are encouraged to make their own decisions. The best known examples in Asia are projects that use Farmer Field Schools (FFS) or participatory technology development (PTD).

It must be noted that there is some disagreement about whether or not the concept and name of extension really encompasses all four paradigms. Some experts believe that the term should be restricted to persuasive approaches, while others believe it should only be used for educational activities. Paulo Freire has argued that the terms ‘extension’ and ‘participation’ are contradictory. There are philosophical reasons behind these disagreements. From a practical point of view, however, communication processes that conform to each of these four paradigms are currently being organized under the name of extension in one part of the world or another. Pragmatically, if not ideologically, all of these activities are agricultural extension.